Technology has always played a huge role in shaping our lives, and it’s clear that modern innovations are often built on the foundation of historic breakthroughs. Many of today’s cutting-edge gadgets can trace their roots back to pioneering products that sparked entirely new categories. One such game-changer was the digital camera once a luxury reserved for professionals and tech enthusiasts in the 90s, both expensive and out of reach for the average person.

Fast forward three decades, and cameras have undergone a remarkable transformation, shrinking from bulky, complex machines to sleek devices that now live inside our smartphones.

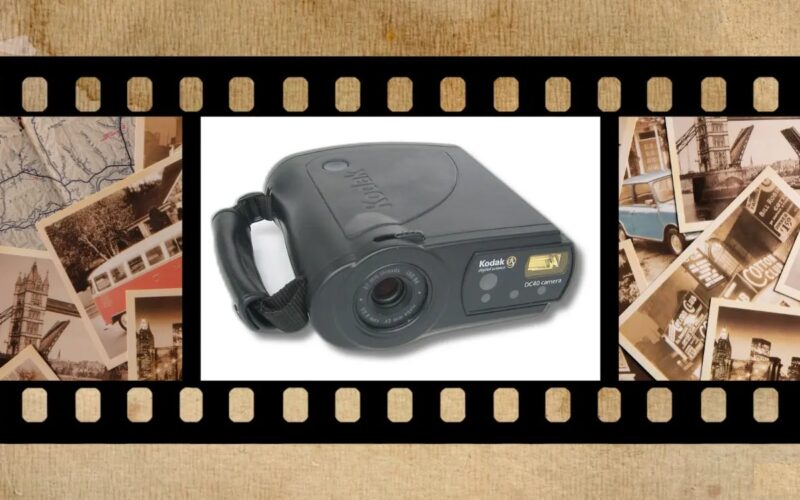

A major milestone in this journey was marked by the launch of the Kodak DC40. Released on March 28, 1995, the DC40 was Kodak’s first consumer-friendly point-and-shoot digital camera. It was the result of years of research and development a follow-up to a historic moment two decades earlier when Kodak engineer Steve Sasson built the world’s first digital camera prototype in 1975. The DC40 made digital photography more accessible to the public and paved the way for what would eventually become a global digital photography boom.

Why Was Kodak DC40 A Big Deal?

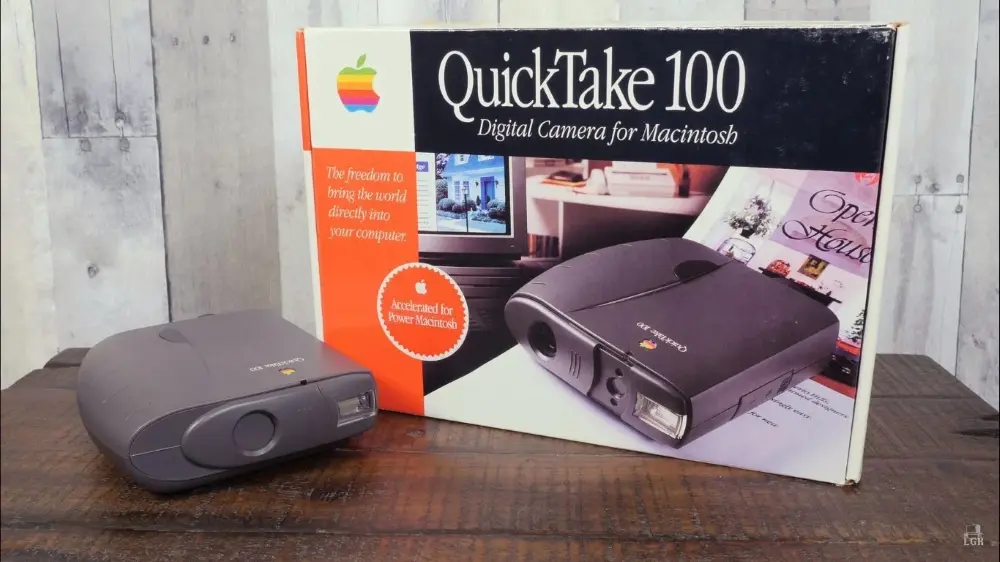

Picture this (pun intended) it’s 1994. Apple had just launched one of the first digital cameras for consumers, the QuickTake 100. Meanwhile, tech giants like Sony and Fujifilm were already experimenting with digital photography, working on their own early models. Then, in 1995, Kodak entered the scene with the DC40. Over the years, many people came to believe that the DC40 was the very first consumer digital camera but that’s not entirely true. What really set the DC40 apart wasn’t that it was first; it was Kodak’s strategic marketing and effort to make digital photography more accessible that cemented its place in people’s memories.

During the era of film cameras, Kodak was a household name in both camera and film manufacturing. The company built on this reputation and the trust it had earned over the years. Their push for the DC40 was strong, and thanks to its impressive specifications, the camera performed exceptionally well in sales. This is how the DC40 became synonymous with the term “first consumer digital camera.”

Accessibility was the key factor here. At that time, film SLRs were widely available. Models like the Leica R4, Nikon F90X, and Pentax Z-1p were all well-known. However, they were expensive, typically priced around $2,000, making them popular mainly among professionals. Even other user-friendly cameras came with a hefty price tag. Digital cameras such as Kodak’s own DCS 460, for instance, cost upwards of $35,000!

There was a clear gap in the market for an affordable digital camera. Kodak seized the opportunity to fill that void with the DC40 and the rest is history.

Kodak DC40’s Technical Superiority

The advantages of choosing the DC40 were clear from the start. It offered a higher resolution than Apple’s QuickTake 100, coming in at 756 x 504 pixels. It also featured a larger 4 MB internal storage, capable of holding 48 low-quality or 24 high-quality images compared to the QuickTake 100’s 32 and 8 images respectively, due to its smaller 1 MB storage. Interestingly, the QuickTake 100 itself was co-developed with Kodak, making the DC40 essentially a better, more refined version of the QuickTake 100.

Another factor that hindered the adoption of the QuickTake 100 was Apple’s exclusivity. Initially, the QuickTake 100 was only compatible with Mac computers, and the images were saved in a proprietary QTK format, which required extra effort to convert them into other usable formats.

Kodak, on the other hand, also used its proprietary KDC format but gave users the flexibility to save images as TIFF or PICT files. This was made possible through Kodak’s collaboration with Microsoft and IBM. The broader compatibility meant that buyers weren’t restricted by their operating system they could use the DC40 whether they were on Mac or Windows.

In the end, Apple’s decision to keep the technology exclusive to its ecosystem ultimately hurt the QuickTake 100’s sales. On the other hand, the DC40’s higher storage capacity, better resolution, superior processing, and the trust people already had in the Kodak brand made it a far more practical choice for consumers. It’s almost bizarre to realize that Apple faced strong competition long before Android and in a completely different industry.

Kodak DC40’s Price Back Then: What Could That Buy You Today?

The Kodak DC40 was priced at $849 about $100 more than Apple’s QuickTake 100. However, Kodak’s superior specifications made the extra cost worthwhile. To put that into perspective, $849 back then would be equivalent to around $1,800 in 2025. That’s enough to buy a top-of-the-line camera in today’s market.

For the same amount of money today, you could get your hands on some of the most beautiful mirrorless cameras available like the Nikon ZF (review) or the Z7 II. Other full-frame options in this price range include the Sony a7R IV and the Canon R6 Mark II. And if you’re looking for something a bit more affordable, you could even opt for a mirrorless Sony a6700.

On a personal note, here’s a Canon PowerShot A310 a camera released in 2004 with a CCD sensor and a 3.2 MP resolution. It originally belonged to my grandfather, and it never fails to amaze me how far camera technology has come. Even after 21 years, it still works!

It’s the camera that captured most of my childhood memories before it was eventually replaced by the Nokia N73. Yes, the classic Nokia way ahead of its time with its Zeiss optics and solid camera performance. It’s missing a battery now, but I’m pretty sure if I managed to find one, it would still power on without a hitch.

What’s Different in Current Setups?

One of the biggest differences between older cameras and today’s models is the shift from CCD (Charge-Coupled Device) sensors to CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor) sensors. CCD sensors were known for delivering images with less noise and higher quality, but they were also more expensive to produce and slower in operation.

Over the years, however, CMOS technology has advanced significantly. CMOS sensors are now faster, more power-efficient, and much cheaper to manufacture. As a result, CCDs are mostly used today in specialized fields like scientific imaging, while CMOS sensors power almost every modern camera, smartphone, and imaging device.

When you think about it, the situation with modern DSLRs isn’t too different from film SLRs back in the day. While they’re a bit more accessible now, they’re still expensive and come with a steep learning curve. Smartphones, on the other hand, are the modern-day equivalent of the Kodak DC40 simple, accessible, and good enough for most people. And over the years, they’ve made massive strides in areas like optics, stabilization, and color science.

That said, we now live in the age of computational photography and social media, where heavily processed images dominate. While smartphone photos may look pleasing to the average viewer, there’s still a clear distinction when compared to professionally shot images. Plus, the flexibility and control that dedicated cameras offer whether it’s through manual settings or interchangeable lenses — makes them the preferred choice for those who want to craft each shot with precision.

The Inevitable Decline: Competition Heats Up, Opportunities Slip Away

With the models that followed – the DC20, DC25, DC50, DC120, and DC240, Kodak put in serious effort to make digital cameras both more affordable and higher in quality. The direct successor to the DC40, the DC50, featured the same 0.38 MP sensor but introduced a zoom lens (34 mm to 111 mm equivalent) along with other improvements like an integrated flash.

The DC120 marked another leap forward with a 1.2 MP sensor, 2 MB of storage, and an industry-first Compact Flash slot for removable memory. Then came the DC240, which delivered the ultimate upgrade a color LCD display, USB connectivity, and an even higher resolution.

While Kodak was focused on advancing its digital photography lineup, its film business which accounted for 50% to 70% of the company’s profits was steadily declining. Ironically, it was this very film business that had been funding Kodak’s research and development in digital cameras. Although film was still thriving in the late ’90s, Kodak began to lose ground as competitors like Fujifilm gained momentum. Fujifilm, in particular, quickly grabbed 25% of the U.S. film market, cutting into Kodak’s sales.

Caught in a dilemma between protecting its profitable film business and fostering its growing digital segment, Kodak struggled to commit fully to either. The company kept diverting profits from film to fund digital development but remained hesitant to let go of its dominance in the film market. That internal conflict paired with resistance to change became a ticking time bomb. The early success of their digital efforts blinded them, and by the time the reality sank in, Kodak’s leadership was already divided, unsure whether to double down on film or go all in on digital.

Kodak’s reluctance to take bold risks, combined with rising competition from brands like Canon’s PowerShot series and Sony’s Mavica lineup, left the company stuck in the middle. It failed to strengthen its film business and couldn’t develop its digital cameras fast enough to match the impressive specifications offered by its rivals.

By the time Kodak realized the gravity of the situation, it was already the early 2000s, and the digital camera revolution was in full swing. More manufacturers had entered the market, the demand for film plummeted, and profit margins on digital cameras were slim due to intense competition. By 2004, Kodak had stopped producing film cameras, and by 2009, it discontinued its film rolls altogether. The decline was so sharp that by 2011, the market had shrunk beyond recovery, forcing Kodak to file for bankruptcy in 2012.

Post-Bankruptcy Transformation

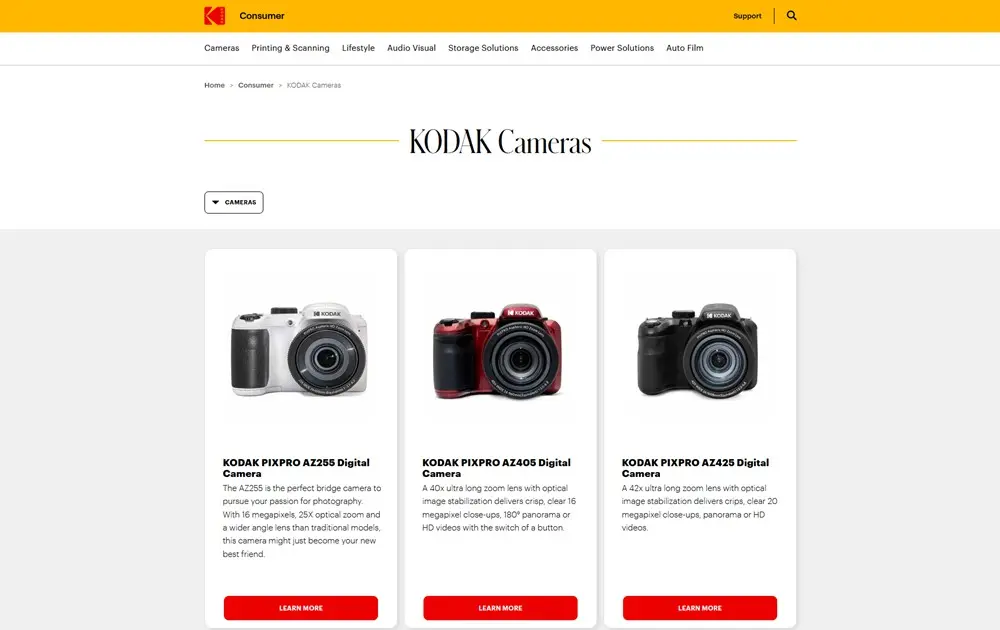

After 2013, Kodak was no longer the camera giant it once was. Following its bankruptcy, the company managed to pay off most of its debt and pivoted to a business-to-business model, focusing primarily on commercial printing. While the film market became niche, Kodak continued to sell film stock, capitalizing on the demand from a few industry players and enthusiasts who still preferred film over digital.

Kodak-branded cameras are still available today, but they’re produced under license by a third-party company called JK Imaging. These include a range of point-and-shoot cameras under the PIXPRO lineup. However, they’re far from competing with the industry’s leading full-frame or mirrorless offerings a stark contrast to Kodak’s golden days.

Kodak DC40’s Legacy Still Lives On

Kodak serves as a classic example of what happens when a company becomes too comfortable in its own success. Had the brand prioritized and fully embraced the digital camera revolution early on, its story might have been very different. While the bittersweet ending of the old Kodak will always be remembered, it’s equally important to acknowledge the impact of its early innovations many of which laid the foundation for the technology we still benefit from today.

Kodak wasn’t technically the first manufacturer to release a consumer-grade digital camera but it was the one that kickstarted the trend. While Apple may have been the first big name to enter the space, for many people, the Kodak DC40 was the camera that truly introduced the public to digital photography.

Interestingly, point-and-shoot cameras seem to be making a quiet comeback today. Their portability, simplicity, and nostalgic charm have driven a sudden rise in demand. Models like the Canon G7X Mark II, Sony’s DSC series (both old and new), and Fujifilm’s X100 lineup have become incredibly popular, particularly among those chasing that retro vibe. Whether this resurgence will last or fade away like many other trends remains to be seen.

From modern point-and-shoots to smartphone cameras and today’s advanced DSLRs and mirrorless systems none of it would’ve existed the way it does without Kodak’s early contributions. At the very least, digital photography might have remained a proprietary or expensive niche technology had Kodak not stepped in when it did. While the brand no longer leads the charge in innovation, photographers, hobbyists, and professionals alike will always owe a debt of gratitude to Kodak for laying the groundwork.